The dividing line between helpers and dissidents is ambiguous if not arbitrary — as documented by you in your responses last week. Often, a specific issue inspires a community that both aims for socio-political and cultural change, as well as offers support (helper) functions. An example of this could be the YouTube-based It Gets Better project, an initiative that seeks to offer support for Lesbian, Gay, Bi, Trans, Queer youth.

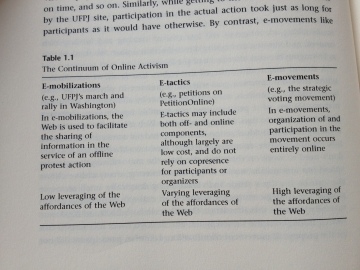

Similarly, there are different modalities of ‘digitally enabled social change’. For example, in their research, scholars Jennifer Earl and Katrina Kimport suggest this continuum of online activism:

Digital Dissidents for Democracy

In terms of major aspirations of radical structural change, and acts of resistance, we all are familiar with the the powerful examples of the Arab Spring, and brave individuals and groups (not only “We Are All Malala” but also “We Are All Khaled Said”). Yet, political Internet activism has long roots, for example in the Mexican Zapatista movement.

Social media have recently brought different opportunities, and challenges, to E-mobilization, E-tactics, and E-movements. Here’s an insightful account by Rasha A. Abdulla, associate professor in the department of Journalism and Mass Communication at the American University in Cairo and one of our experts in this course: ‘The Revolution Will Be Tweeted‘. Read her account of Egyptian Spring — and if you’d like to ask any questions, please post below!

Movements have gone global because of digital media. Arguably, the Occupy Movement, for example, has used an interesting mix of communicative tools and media, from hand gestures to online and mobile organizing — but certainly spread around the world because of social media. (Here’s a fascinating account of the birth of the movement). Occupy Sandy broadened the movement from protesting to doing hands-on disaster relief work. It also spurred a collaborative documentary project.

have gone global because of digital media. Arguably, the Occupy Movement, for example, has used an interesting mix of communicative tools and media, from hand gestures to online and mobile organizing — but certainly spread around the world because of social media. (Here’s a fascinating account of the birth of the movement). Occupy Sandy broadened the movement from protesting to doing hands-on disaster relief work. It also spurred a collaborative documentary project.

Other times, social media platforms feature more spontaneous political reactions and protests, such as the infamous YouTube Muhammad video and its tragic aftermath — and the related Twitter response #MuslimRage that followed, as a protest to a mainstream media story (a condensed account with a great discussion and a slideshow on HuffPost).

This excellent article from The Guardian showcases an array of examples of political digital humanitarianism (my term, but I’m sure you know where I’m going with it). The blog iRevolution, mentioned in the article, is one of my go-to sources of all things techie assistance from disasters to revolutions.

Media Reformers

But we have also discussed how, sometimes, digital platforms are not only tools for democracy, but tools for surveillance by non-democratic regimes (remember Clay Shirky and Evgeny Morozov debating in this blog post of the Weeks 3-4).

And that leads us to a very particular form of digital community-building for social justice, the one by those communities that are concerned about our digital (human) rights, and reforming the media themselves, for a more democratic world (the terms often used are Media Reform and Media Justice).

Here’s a short and simple video I did (for a group of Freshmen students) on digital human rights; here’s a related blog post.

In some cases, and countries, media reform efforts take an organized, official form. An anti-copyright movement transforms into a political party, as in the case of the Pirate Party that is active in numerous countries (Dahlgren’s ‘protopolitical’ turning into officially political).

Although internet access and digital divide are often considered as basic questions of infrastructure, and hence most often considered as the responsibility of national governments (and activism seeks to change those policies), there are numerous free wireless and mesh network projects (see also comments for week 5!).

In other cases, issue-driven global communities are formed to counter corporate-driven Internet. Some advocate for, and create, open source code; others wish to create a global community that wants to share their creative work with a self-defined licensing, not by corporate-owned copyright.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2BESbnMJg9M

Back to Basics: Internet Freedom

Yet others are fear for diminishing freedom of the Internet itself. Apart from blatant censorship and dramatic government responses such as the recent one in Syria, there are more ‘subtle’, yet no less important, challenges. Here’s a short video by the journalist/researcher/global internet freedom activist Rebecca MacKinnon (once more — she’s a favourite — in the Oslo Freedom Forum). Using TeliaSonera as a poignant example, she’s discusses her concern about the ways in which commercial imperatives and business practices may, in fact, endanger free online expression.

Here is an extensive list, compiled by Rebecca, of global and national organizations  (communities?), that work for maintaining the freedom of the networks. (Perhaps you’ll find inspiration from the list for your country case?)

(communities?), that work for maintaining the freedom of the networks. (Perhaps you’ll find inspiration from the list for your country case?)

And Personal Democracy Media, the TED-like organization of practitioners, scholars, activist, policy-makers already mentioned earllier, offers great video lectures on Net Policy & Activism. The videos showcase how important media policy-making has become in terms of democracy (and possibilities of community-building), and how it thus become a great interest to media-focused activism.

Incidentally: Today, the 3rd of Dec 2012, marks the beginning of an international conference — in which the world’s leaders will discuss the future regulation of the internet. Many online and offline communities are not too happy about the lack of transparency and of civil society participation in this ITU-driven gathering. Why? Here’s one brief explanation in a video format.

Hacktivism

Yet, there are also are those who wouldn’t be interested in participating in global deliberations, but who use direct digital actions to make their voices heard; those whom some call cyber-terrorists, others hails as freedom fighters: The Anonymous and other hacktivist groups. Here’s a great article by the anthropologist Gabriella Coleman on the nature of the Anonymous as a community — “Our Weirdness is Free”. And here’s a Wikipedia timeline on the activism of The Anonymous.

Yet, there are also are those who wouldn’t be interested in participating in global deliberations, but who use direct digital actions to make their voices heard; those whom some call cyber-terrorists, others hails as freedom fighters: The Anonymous and other hacktivist groups. Here’s a great article by the anthropologist Gabriella Coleman on the nature of the Anonymous as a community — “Our Weirdness is Free”. And here’s a Wikipedia timeline on the activism of The Anonymous.

These are all concrete examples of the transformative power of digital media. But they still are relatively isolated experiments, digital communities for social justice only in the making. So the question becomes: Are we, postmodern individualist humans, capable of working together for true freedom and equality? Now that we know more about the world, and connect more easily with others, than ever before in human history — can we really accept others? Or are online communities temporary and fleeing constructions?

Assignment for this week, due by our meeting on Tuesday 11 Dec:

- We will get together at Siltavuorenpenger 1 PSY Sali 2 at 10 am for a fascinating Guest Lecture (yet another angle to community building!). We’ll break for lunch and meet again at 13hrs to discuss what we’ve learned from a particular case study of a community formation (The Anonymous) and from our collective country cases. We’ll finish by 15hrs. So, by 11.12.:

- Explore the blog post (lots to read/watch).

- Watch We Are Legion

- Read at least 2 of the following (any 2 — or all, if inspired): Jansen (in Dropbox, Chptrs 10, 11, 12) = Sullivan (open software), Andrejevic (surveillance), Martin (defending dissent); from the Social Media Reader (in Dropbox) = Coleman (hackers/trolls), Lessig (free culture – copyrights); articles in Dropbox: Muller (It gets Better – the YouTube project); re-read Youmans & York.

- There are also a couple of additional resources, just for fun – “Extras” in our Dropbox: Reports on 1) social media in revolutions and 2) Freedom of Expression around the world, as well as 3) a handbook for safely producing media as dissidents, and 4) a ‘cyber-dissident’s handbook’. For you to explore if you’d like to.

- Add to the google doc: any dissidents / media reformers in your country?

- Comment below about any major/minor takeaways of this week re: your country and/or more generally.

- Read other people’s comments here and on our google doc about their countries — be prepared to discuss on 11.12.

- Want bonus points? Inspired by Chris’ comments on gamification (see Week 5), here’s an opportunity: Go ahead and explore a game at www.gamesforchange.org — and share your thoughts briefly below.

- NOTE: Would you like to discuss your final paper in person? Book a time from Minna for Mon 10 Dec 13-15hrs. You can always also email and / or skype, anytime.

As we didn’t have enough to read, but I couldn’t resist: Just came across this great mini blog post anthology on the dark side of DIY activism (Kaisa!!!!)

http://henryjenkins.org/2012/12/hot-spot-the-dark-sides-of-diy.html

By: mediastudies2point0 on December 4, 2012

at 3:52 pm

And… A list of initiatives to watch out for… https://www.accessnow.org/blog/2012/12/04/announcing-the-access-tech-innovation-prize-finalists

By: mediastudies2point0 on December 6, 2012

at 6:59 pm

In particular, according to the report of ” my country”, Sweden, there is no significant digital activism. i was thinking that in Sweden as a democratic country, people do not see the necessity of digital activism, because the might see the society open enough to express themselves. On the other hand, in less democratic countries people turn to digital communities as an opportunity, but its vague whether digital communities play a significant role in social or political changes because in these countries, there is a wide digital divide, people do not have access to computer devices and Internet equally and government usually turn to surveillance and filtering of online communities.

i would also like to answer the last questions of this post form my own point of view. I assume that digital communities provide people with diverse information. followers of digital communities are aware of events that is happening around the world. digital communities rise their awareness about the issues that have existed for a long time, but these issues are now in front of people’s eyes.it is controversial if we claim that increased awareness leads to actions. Also, despite from governmental censorship, digital communities are sphere for non-democratic, sexists, racists and other unequal ideas. i know lots of Facebook pages that reproduce inequalities and barbaric ideas, people just bring themselves to digital communities as what they are in real world, they have the same receptivity that they show in their daily life in offline communication. I think that online communities are effective temporary and for taking certain actions by certain people.

By: Banafsheh Ranji on December 7, 2012

at 11:07 am

The Pirate Party? From Pirate Bay to the parliament. (Not your conventional activism, but an interesting case… Check out the documentary on YouTube).

By: mediastudies2point0 on December 7, 2012

at 11:32 am

Here’s some of my thoughts on this week’s topic:

Just like digital helpers and cultural collaborators, that we were discussing last week, there is at times only a fine line between digital dissidents and media reformers. For example the hacker community Anonymous could well be considered to be either one (or both) of those.

Personally I find the work of Anonymous interesting and weirdly fascinating, and thus I thought the film ’We Are Legion’ was really worth a watch. The documentary together with Gabriella Coleman’s article ’Our Weirdness Is Free’ really gave a good insight into the community, its history and its goals.

In her article, Coleman asks the question ’How and why has the anarchic ”hate machine” been transformed into one of the most adroit and effective political operations of recent times?”. The power that nowadays lies within the Internet and its digital platforms is a key answer. Most of the world’s essential information is stored in the Internet and is therefore a potential target for hacktivists. The ”hate” that the Anonymous perhaps once had, can now easily be transformed into direct actions, whenever something comes up that catches the community’s eye. As stated above and as Coleman also writes, ’Anonymous has devoted its energies to digital dissent and direct action’. This dissent and action is mainly directed towards doing good – Anonymous target people and corporations that they find morally questionable (the Church of Scientology, Egyptian government, Hal Turner etc.) and therefore they can be seen both as media reformers and digital dissidents as well as digital humanitarians.

Anonymous is naturally also known in the UK, my country of choice, but to my knowledge, none of the world’s most famous hacker groups originate from or are based in the UK. However, there is no doubt that Anonymous and other groups have a lot of British members too.

Another interesting example mentioned in the blog post this week is the ’It Gets Better’ YouTube campaign. In her article about it, Amber Muller writes how the campaign and its consequences are evidence that the online engagement is inseparably linked to physical reality and social construction. This can also be seen when looking at Anonymous – especially the attack against Scientology gathered thousands of members worldwide to form a more conventional protest.

Just like I mentioned last week when talking about digital humanitarians, joining global movements is typical of the UK also when it comes to media reformers and digital dissidents. Platforms like Twitter are also full of digital dissidents, especially people criticizing politicians and stating their opinions to current political topics. There is also an actively functioning Pirate Party in the UK, which can be considered one of the most important media reformers in the country.

This might be a slight simplification, but I think all in all digital activism is more typical of developing countries than democratic developed countries like the UK. That’s why developing countries in general tend to offer more interesting national examples of digital activism communites, whereas developed democracies tend to take part in global communities instead.

To answer the question stated at the end of the blog post, I remain quite optimistic and in my opinion it is possible for postmodern people to work togehter for true freedom and equality. The internet enables global actions – a great example being the Anonymous’ attack against the Egyptian government to support the Egyptian people who were protesting in the streets and striving for democracy. The Anonymous had no responsibility to do anything and still they decided to help. The same thing can be seen with many digital communities, especially the digital humanitarians. Still, the digital community needs to be based on real-life action – somebody needs to be prepared to help also physically, not only by clicking a button.

By: Emmi Lehikoinen on December 7, 2012

at 2:02 pm

I found your post really interesting Emmi, however, I would have to disagree with your point about digital activism being more typical of developing countries rather than democratic developed countries like the UK.

A really interesting story that has come out of the hacker community in the UK is that of Gary McKinnon (http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-19946902). He was arrested following allegations from the US that he had hacked into US military computer systems in an attempt to bring them down.

For the past ten years he’s been fighting extradition to the US and claims that he was merely investigating UFO sightings in a “moral crusade”. He is now somewhat of a figurehead for the hacking community in the UK and the government has recently refused the US extradition order.

There is a much more detailed analysis of the case on the guardian if you’re interested:

http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/gary-mckinnon

By: chr1sdenholm on December 10, 2012

at 3:12 pm

Thanks a lot Chris, I had completely missed this! Seems very interesting, I’ll have to look into it.

By: Emmi Lehikoinen on December 13, 2012

at 9:26 am

China, “my country”, is a very juicy subject when discussing digital dissidents, media reformers and internet freedom. Therefore I mainly focused on China on this week’s assignment, although there’s lots of interesting stuff on a global and general level, too. Anyway, here are some thoughts and examples on China related to this week’s topic:

It has been said that China has the most effective and extensive systems for internet censorship in the world, i.e. very limited internet freedom. With the Great Fire Wall and active censorship, thousands of websites are blocked, including Facebook, Twitter and Flickr and many search engines (Google, Wikipedia and YouTube are open with certain restrictions set by China). The system filters URLs (including censoring keywords such as “democracy” and “human rights”), monitors the largest blog and micro-blogging platforms. Even words such as “Egypt” and “Tunisia” have been censored after the uprisings, as the Chinese government felt that the country’s stability was at risk – not to mention the effect of the Nobel Peace Prize won by Liu Xiaobo in 2010. The Chinese government in fact has tried to tighten it control over the internet for example by denying online anonymity.

According to Reporters Without Borders, China jails more digital dissidents than any other nation. China is even listed on the “Enemies of the Internet” list, held by RWP (http://en.rsf.org/internet-enemie-china,39741.html). Questions about safety naturally concern digital dissidents, as people who express undesirable information against the Chinese government and Communist Party are punished and invited to “drink tea” (means being questioned) by the police.

Even though being a digital dissident or a media reformer in China’s cyberspace is tricky and dangerous, Chinese don’t seem to give up on fighting for their rights and freedom of speech, freedom of information and freedom of internet. They seek for alternative ways to express themselves online, ways that don’t get caught by the censors – at least that easily.

As I mentioned in my comment last week, humor and sarcasm is a popular way to “fool” the Great Fire Wall. People use proxy websites to access restricted websites and information anonymously (see for example Access Now referred to by Carne Ross in his Guardian article). In 2009 a Declaration of Anonymous Netizens spread in China’s cyberspace calling for netizens to express and protect their anonymity on 1st July (http://advocacy.globalvoicesonline.org/2009/06/24/china-2009-declaration-of-the-anonymous-netizens/). This campaign was introduced especially in reaction to the introduction of Green Dam, a censorship programme.

The active network of netizens, citizen journalists, and professional journalists blogging online are in a way reforming the media system in China. By offering news from the “outside world” they are challenging the traditional state-controlled and propagandist Chinese media. There are loads of voluntary people trying to filling the gap of information in China; not only because of the internet restrictions but also because of language barriers (for example, see the Yizhe group http://yyyyiiii.blogspot.com/). There are also sites that offer up-to-date news on China to the rest of the world, including news on human rights, politics, society, etc. (for example, see http://chinadigitaltimes.net/about/).

China’s current situation is also on the agenda of many international movements/campaigns that aim for internet freedom. In the end, internet makes global actions possible. For example the Anonymous targeted Chinese websites in March 2012 to make a statement about internet freedom (http://chinadigitaltimes.net/2012/04/anonymous-hackers-take-on-the-great-firewall/). But, as I said in the beginning of my comment, the Chinese government keeps on fighting back by tightening the restrictions. So, is it only a never ending vicious circle between revolution and repression or will there be a significant change towards better?

I think Emmi is on to something with her idea that online activism flourishes more in non-democratic countries; China acts as a good example here. Democratic countries, then, take part in fighting for justice in these countries in order to someday hopefully reach equality in internet freedom. This occurs in the offline world, too: third world countries, activists and volunteers help the countries in need, offer humanitarian aid, protest against wrongdoing, and show support for dissidents, etc. As to the question on true freedom and equality on global level, it does seem a bit idealistic and utopist. But at any rate, cynicism and pessimism doesn’t get us anywhere. In the end, small streams make big rivers.

By the way, I checked out the gamesforchange.org and tried to play one game, but that one didn’t work. I’ll take another try later. Anyway, I find the idea of the site really inspiring: that with games, traditionally seen as entertainment, you could raise awareness on important social issues. This could work especially on people who normally wouldn’t take part in “making good” or be interested in such issues. Also good for educational purposes!

By: nooraha on December 7, 2012

at 3:27 pm

Online activism of any kind has two sides to it. On one hand, it is a great possibility for democracy, for humanitarian aid, for informing or even mobilizing global audiences for a good cause. On the other hand, there is little evidence on the success of these kinds of initiatives on a larger scale.

Now, I’m not saying there are not many examples of successful initiatives for digital humanitarianism, as all of us evidenced last week in our comments, or that the internet cannot work as an acceleration lane for democracy or even showcase the end of oppressive governments. Yet, the risks with announcing internet as THE solution to these kinds of problems combined with the technological determinism are quite big. With digital humanitarianism and digital activism in general, often the technology is given main priority. Rasha Abdullah said in her article that yes, the internet can be labeled the main catalyst for the Egyptian revolution even though it wasn’t the only factor involved nor were internet protestors the only ones: “the Internet was the tool that showed every dissident voice in Egypt that he or she is not alone, and is indeed joined by at least hundreds of thousands who seek change.” The power of the internet is in its ability to connect people, but in order to work together for true freedom and equality, if possible as Minna asked, there have to be people who are motivated, who have a common goal and who are willing to put effort into achieving this. Furthermore, there have to be people who act, not just participate. This idea of people as the power can be linked to the idea of DIY activism via the internet (http://henryjenkins.org/2012/12/hot-spot-the-dark-sides-of-diy.html). The idea that we need to act beyond governments’ actions and other “official” activism also has its downsides: us humans never really did anything completely by ourselves, so it’s silly to think we would do so now. Kjerstin Thornson writes (http://civicpaths.uscannenberg.org/the-dark-side-of-diy-figure-it-out-for-yourself/) that the DIY discourse about news and politics raises the bar for “the non-wonky, the politically uninterested, the people who have better or more required things to do than check their iPhones for the latest AP wires or follow the ever-growing number of breaking news rock stars on Twitter.” She continues we should “stop setting the bar of informed citizenship so high that lots of people won’t bother paying any attention at all.” This evidences that those uninterested or incapable can “fall over board” from the ship loaded with social media, new technologies and do-it-yourself activism. What Thornson argues is that the fall might be so hard they don’t want to get up anymore but stay passive towards news and politics in general.

The biggest problem is thinking the internet is inherently democratic and it will sort of solve many of the modern society’s issues almost by itself. Funny enough, this is something the critics of the internet as a tool for building social communities imply, as Amber Muller claimed in her article on the It Will Get Better -project. She quoted Wellman and Giulia (1999) saying these critics “almost always treat the Internet as an isolated social phenomenon without taking into account how interactions on the Net fit together with other aspects of peoples’ lives, the Net is only one of many ways in which the same people may interact”. The internet is valuable only in the ways people use it: digital communities (nor digital activism for that matter) are never completely separate from real life. The members of the Anonymous realized this when they mobilized to protest against Scientology – in We Are Legion they tell they were surprised to see themselves in such great numbers. Finally, they got a harsh reminder on the connectedness of the digital and the real world when members were sentenced to prison for their actions. Don’t get me wrong, I think the Anonymous is a fascinating group who are more good than they are bad. Nevertheless, the thought that one “forgets” one’s online actions actually also affect “the offline world” (not that this division is anything but artificial) is quite scary in that it reminds about the complexity of the human mind and how it works in different circumstances (remember the Milgram experiments – when one is physically separated from the target of one’s actions, it is a lot easier to make decisions we wouldn’t make in person). As we have discussed, internet can just as well be used for undemocratic ends, not to mention the fact that the digital divide is still strong even though broadband access has been added to basic human rights in many countries (yay for Finland being the first one!).

The debate on the ability or inability of people to work together or accept others aside, there are less philosophical and more concrete factors hindering this process. Lawrence Lessing writes in his article REMIXED about how the old-fashioned way of approaching new technologies is reducing that thing we have for so long hyped to be the democratizing and innovative aspect of internet: he claims strict copyright laws are reducing a new way of expressing creativity in the modern society. Firstly, I must admit his was the best-written academic article I’ve read in a while, maintaining its wit even though remaining academic. Second, new technologies have always brought fear and moral panics with them and the internet is no exception. The internet is even a bit special in this way; since still today new ways of using it are invented and it isn’t always clear what kind of effects these have – not to mention the security issues. For example, Anonymous shut down PayPal and hacked loads of personal e-mails and put them out there for all the public to see. The Anonymous’ intentions were pretty harmless and they only wanted to stand up for what they believed in. But they also brought into everyone’s attention that a large amount of technical intelligence put together can cause serious trouble – what if all terrorist organizations would have this kind of tech support? Therefore again we come back to the complex relationship between security and surveillance.

The idea of “remixing” and the security-surveillance issue also come up in the examples of Poland on Rebecca MacKinnon’s list. Remixing includes the idea that with less strict copyrights we can benefit from each other’s work without making it an issue of commercial interest. Remixing is interestingly also mentioned on Modern Poland Foundation’s site. MPF is an organization that aims to developing modern educational methods and advancing Poland in its way of becoming an open information society. On remixing, they say that “during the last two years we have run many projects related to the remix culture in which we try to combine creating high-quality educational materials (including audiobooks), with teaching of creative skills required for remixing cultural goods.” The security-surveillance issue also arises from Poland’s example “digital activist” organizations. As I already mentioned in my comment last week, the ACTA (Anti-Counterfeiting Trade Agreement, check http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anti-Counterfeiting_Trade_Agreement) stirred lots of resistance in Poland. Thousands marched on the streets and even in the parliament the libertarian Ruch Palikota party protested: http://www.politics.ie/forum/europe/180593-anti-acta-protests-break-out-poland-thousands-take-streets.html. One more example is the Panoptykon Foundation which monitors legal solutions, both those in force and those proposed. They say they “analyze them from the point of view of the right to privacy and respect for human dignity.” This might be a false illusion, but all these examples have made Poland in my eyes seem quite modern and liberal in the human rights-internet-surveillance/security axel – even though Poland’s television is not even digitized yet because of disagreements between interest parties. Perhaps it is a sign of the gap between generations, where the young people are actively fighting to make Poland a modern information society and the older generations are less interested or even against that kind of changes – but this is merely my own assumption.

By: Kaisa on December 7, 2012

at 5:55 pm

The Right2Know (R2K) campaign (http://www.r2k.org.za/) is a good example of digital dissidents / media reformers in ”my country”, South Africa.

The campaign (launched in 2010) is a coalition of organisations and people responding to South Africa’s “Secrecy Bill” (Protection of State Information Bill).

The Bill is a highly controversial piece of proposed legislation in South Africa. The Bill aims to regulate the classification, protection and dissemination of state information, weighing state interests up against transparency and freedom of expression. There are allegations that press freedom in South Africa is under threat due to the Bill.

According to the campaign, The Secrecy Bill is a symptom and symbol of much broader obstacles to the free flow of information. These are not merely the rights of journalists or the privileges of an economic elite: free expression and access to information are the building blocks of an accountable democracy.

Currently, the Bill has been passed by the National Assembly and the National Council of Provinces are debating the law.

The R2K campaign has over 6800 likes on their Facebook page, an active Google group, and nearly 5300 followers on their Twitter account. This is very different from the numbers I presented last week about The Treatment Action Campaign and Abahlali baseMjondolo, both relatively well known in South Africa. Over 400 civil society organizations also support the R2K campaign. The campaign has the possibility to follow its actions via SMS. This seems to be typical for many SA digital communities due to the digital divide / poor coverage of internet in the country. Email is also an important form of communication for the campaign.

Digital media platforms are very important for the campaign (freedom of speech online which is not controlled by traditional media what to publish and what not).

The R2K campaign is carried out by digital dissidents in South Africa:

“For all we have achieved, let us remember we only pay two national staff and a few provincial coordinators. The lion’s share of the work in the past year has been carried by activists giving their time and energy to selflessly build the campaign. Our campaign activists and supporters are our greatest strength. We must defend the participatory and activist nature of the campaign”, tells the R2K website.

The campaign has united people across geography, across sectors, across South Africa’s segregated landscape of race, class, and language. The campaign has broadened its scope to tackle related issues.

I also had a look on the gamesforchange.org site. It would need a killer app for a breakthrough for this site. What a brilliant idea to combine games and charity.

By: Anni Jakobsson (@AaJee82) on December 8, 2012

at 12:00 pm

For last week’s activity, I had cited as an example of an online helper the event wherein Albanian Prime Minister Sali Berisha announced to propose a same-sex marriage law in 2009. But it was been revised to just the protection of gay rights during the actual declaration of the law in 2010. This change can be attributed to online activities such as the video commentary (which garnered lots of comments) that had criticized the original proposal.

In line with this, an 18-year old online activist was arrested in Albania early this year, though it was not proven that he was the one who defaced the Prime Minister’s official homepage. Two stick figures engaging in homosexual activities where Berisha’s face is depicted in one of the characters’ head became the content of the web page. The accusation was just been based to Alastor’s other blogging activities, which are mostly about the government’s economic policy. (Full article on http://z9.invisionfree.com/21c/ar/t11132.htm).

In another article, it is stated that Berisha once again became a victim of the internet when a spoof government site was created showing him seated next to Hitler.

Another example of hacktivism activity that Albania was involved with was the ‘Cyber Battle of Kosovo’. Here, pro-Serbian hackers attacked Albanian government websites including Albania’s National Post leaving the message “Kosovo is Serbia” and a Serbian flag. As a counter-attack, individual Albanian hackers also started defacing Serbian websites (or vice versa? Who made the first attack is not clear yet).

Through hacktivism, individuals or groups can openly express their ideas mostly against the government and government rules. But it doesn’t always give a positive result.

By: Marie Christine Angan Acmo on December 9, 2012

at 10:25 am

Speaking about Russia, as I mentioned in our google doc, there are some parties which realised themselves as “reformers”. However, they are not so active.

Thus, we have the Pirate Party of Russia as a political party based on the model of the Swedish Pirate Party. Despite the board elected and statutes voted they still need to work in order to be fully recognized as a party. The official website: http://pirate-party.ru. The main goal of the party is to defend the users’ rights. Also their slogan «for the freedom of non-commercial exchange of information». Also in Russia there are some more or less the same parties in a sense of media reformers such as Left Front (2008) – coalition of the previous members of the USSR, Party of popular freedom (2010) their slogan is «For Russia without lawlessness and corruption». But still, all of these parties are not very popular and well-known in Russia among population.

By: Anastasia Ptashinskaya on December 9, 2012

at 11:57 am

The long-lasting video We are legion covers all the aspects, which are connected with a movement Hactivism. To be honest, I haven’t heard about it before our online course. For me it was very curious and interesting to watch the video. The movie represents the clear ideas of the hactivists. As I got it right, their main goals are to achieve the freedom of the speech in the online environment and also they are fighting for their rights and beliefs.

As far as I am concerned, the idea of freedom speech is not a new one and many people and groups tried to carry on it into mass. I as an European citizen I am ‘for’ the different kinds of activism and it doesn’t matter whether it online or offline. However, one guy in the film said that they (hactivists) don’t have the leader. Due to this I don’t think that crowd can operate properly without lets say pacesetter. As a Russian person I suppose that not everybody should have the opportunity to express their opinions because some people may be not very smart or even they may not be aware of the important things in the sphere, which they want to comment on. Or somebody even may have some mad ideas. As a result it may lead to some unstable situation within society. It is just my point of view, maybe I don’t really understand the issue.

Finally, I believe that the desire to be anonymous by many people in the Internet is not only widespread, but also is a logical one. Indeed, people fill more freely and independently while others don’t know their names.

By: Anastasia Ptashinskaya on December 10, 2012

at 9:58 pm

As I mentioned in last week’s comment, Thailand is quite interesting country in the case of digital dissidents because the Thai government has been limiting the freedom of speech a lot also online. According to the Press Freedom Index 2011 by Reporters Without Borders Thailand has one of the toughest censorship laws in the world, ranking it 153 out of 178. Thailand was also the first nation supporting Twitter’s censorship of tweets in certain regions. Tweets from Thailand could be blocked at the request of an individual, a company, or the government but could still be seen by users in other countries. (http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2012/jan/30/thailand-backs-twitter-censorship-policy%20http:/www.google.com/hostednews/afp/article/ALeqM5gknUp_qtxnJN8-p8Au7tDCE3U0_w?docId=CNG.7e1076302497b7980031a0eadac1fa0b.111)

There is (or at least has been in January, I haven’t tried it myself) an easy way to bypass the country-based restriction (http://thenextweb.com/twitter/2012/01/27/worried-about-possible-restrictions-on-twitter-heres-how-to-get-around-them/) but still Reporters Without Borders has been criticizing the site’s action and feared that Twitter may be drawn into a spiral of censorship imposed by increasingly repressive legislation.

I briefly noted expat dissidents in my previous comment and thought it would be an interesting topic to research a bit more. It wasn’t that easy to find information but I stumbled upon a project called New Mandala, a site which provides analysis and new perspectives on mainland Southeast Asia. (http://asiapacific.anu.edu.au/newmandala/) The site is run by two academics from Australian National University (ANU) College of Asia and the Pacific. In addition the site has country editors, guest contributors and comments by readers.

A recent well covered case by the New Mandala was an anti-government rally organized by the Pitak Siam Organization. (http://asiapacific.anu.edu.au/newmandala/2012/11/27/the-smell-of-teargas-in-the-morning/). Unfortunately this was not written by an expat dissident but by a German photographer-correspondent. But when reading about the Pitak Siam Rally, I thought that maybe these correspondents could be seen also as digital dissidents. There is definitely nothing new with correspondents but the use of new tools and media has definitely changed their role. For example the author Bangkok Pundit is using the new media as tools and remains anonymous. (http://asiancorrespondent.com/author/bangkokpundit/) Bangkok Pundit is a blogger and tweeter who runs the leading English-language news blog in Thailand. The blog started in 2005 and has daily about 5000 visitors. (http://prachatai.com/english/node/1606)

By: llaavakari on December 9, 2012

at 12:11 pm

As already mentioned, Turkey is a country where censorship of access in the web is rather usual. As noted in previous week, there were cases when the authorities banned access to YouTube or even to Google results for reasons that were related to the religion or to the history of the country. Although, there seem to be a lot of movements that are try to promote the right for free internet access in the country.

It is worth mentioning that in the summer of 2011, 32 men arrested in allegations of being part of the anonymous hacktivist movement. Of course, this is no news, not only in Turkey but everywhere in the world.

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/technology/news/8573407/Turks-arrest-32-alleged-Anonymous-hacktivists.html

Last April, there was also an incident, when Turkish authorities plug out the internet access, since they couldn’t cope with an attack on the webpages of the Turkish police and the ministry of justice. The attack seemed to be the result of the cooperation between anonymous and RedHack, “a Turkish leftist online group founded in 1997” which supports freedom of the internet. http://istanbulian.blogspot.fi/2012/04/when-hacktivism-strikes-turkey-pulls.html

Redhack seems to be the most famous example of hacktivism in country but there are also a lot of groups that they are supporting freedom of the internet. After all, Turkey is very strict on ts rules over internet access, so even if someone believes that hacktivism is not the right thing to express your disagreement, it is obvious that at least the perception over internet access should be changed

By: Laida Limniati on December 10, 2012

at 2:37 am

As for Games for change, although I didn’t have the time to enroll in any game, I follow the work and the beliefs of Jane McGonigal for a lot of time and I really admire her thoughts. After all, they are a lot of people who spend a lot of their time playing. Why not extracting something good and productive out of it?

By: Laida Limniati on December 10, 2012

at 2:42 am

First, I want to talk about Georgia and its digital political activism. E-mobilization in Facebook in Georgia. In country where traditional media are totally under control of government, there is no freedom of speech and any attempt to organize people for protest could fail, cyberspace is giving an opportunity to avoid this control. The same things happened in Ukraine (that is why I choose Georgia, because this country is pretty similar to Ukraine in terms of digital activism and digitalization processes). Different protest movements rather organize themselves in Internet then in real life.

E-tactics activities happened because very often it’s easier to reach people online and attract an attention of public. In Internet you can be creative and people will like and share you post, activity, they will talk about that. Information is spreading like virus in social networks. Even if they do not care that much, some people participate.

More interesting for me in political activism in Internet is opinion leaders. Most of the time beginners of movement are some kind of opinion leaders in some areas and they have power to influence directly their communicative networks. They start the process and then it’s spreading faster and faster.

Anonymous

When I was reading Gabriella Coleman’s article about Anonymous movement and watching film “We Are Legion” I understood that only few weeks ago I saw it already. In the last part of story about Agent 007 James Bond. There was a bad guy, who easily planed all attacks just by broking into systems with the highest security systems. What is more, he posted secret names of agents on YouTube. Isn’t it the same scenario? And this story is pretty old. Anyone who can easily hack the system get the power under the most powerful. And now this is not only fiction, it is our reality.

Anonymous is not about being unknown, but it about freedom, free communication among people, safely and securely. No boundaries, no time limits, no power relations. It seems that it is a global community in new cyberspace world.

In a web-page of Rebecca MacKinnon’s book in “Get involved” page we could see that people are looking forward for free cyberspace and numbers of organizations that are fighting for digital freedom are constantly growing.

Anonymous is very good example of digital community. As Coleman wrote, “Anonymous includes hard-core hackers as well as people who contribute by editing videos, penning manifestos, or publicizing actions.” Thus, people participate because they want to do that, they are interested, they act on a basis of free will. Moreover, as we saw in film, participants care about things in this community, they “feel very deeply and very sincerely about their contribution”. In Anonymous community people can find understanding and support: “I don’t care about your religion, orientation, occupation. It just your opinion that matters”, “…it is one voice”, “It is collective”. All features of Anonymous as community make it perfect if you are interested in their movement.

By: Svitlana Kisilova on December 10, 2012

at 9:21 am

It seems to me that in The Netherlands there aren’t as significant scene of digital dissidents as one would think of. It’s rather hard to find specific groups and one of the few is Bits of Freedom (Bits of Freedom is the Dutch digital rights organization, focusing on privacy and communications freedom in the digital age. Bits of Freedom strives to influence legislation and self-regulation, on a national and a European level. Bits of Freedom is one of the founders and a member of European Digital Rights (EDRi). https://www.bof.nl/home/english-bits-of-freedom/). For a very diverse country it seems weird that there aren’t a whole lot more civic activism online (or offline) to raise awareness of different issues. It looks like the dissidents come more from the official side than from the civic activists. The Netherlands passed a law this fall about net neutrality – companies cant censor content online anymore and free software (such as Skype or WhatsApp) will remain free. They haven’t reported any long-term outcomes yet, but this could potentially mean great things for activism since all the information is available online for everyone. The change isn’t so drastic, since the Netherlands has been relatively open already, but the country is the second in the world to take a stand like that. So it seems that even if there isn’t a whole lot of civic online activism, I wonder if the activism comes from the official parties. Could it be that the individuals don’t have same kind of needs for activism since the government protects some of their rights? Even the country report about the Netherlands pointed out that the country has had some trouble getting official stands on issues, since the country seems to be spread into two different ends – the very liberal end and the more conservative end.

I took a look at the games (http://www.gamesforchange.org/play/) and found them interesting. Most of the games are for kids or teenagers, so they probably work better for them. I tested a couple of the games and it seemed that the game was more important in them than the message they wanted to get across. The games had an educational part too, but not in a way that a child would stop and read it. For example, a game about sexual minorities (A Close World) is a game where you walk in a forest and come across monsters who seem to offend you about your sexuality. You won’t see the insults and you can fight back with “logic”, “empathy” or by “passion”. You only get to choose from these options, but you can’t see the argument that you’re making. If we want to teach kids how to fight oppression, wouldn’t it be good to show them examples on how to use logic or passion to make your statement? The games were also done in a way that the player couldn’t really change the outcome, and therefore the message was probably buried under some clicking. So, at least the couple of games I looked into might be educational and fun for kids but not for older people. These games were free but a good way to raise awareness would be to donate all the proceeds to non-profits or something like that. The one’s who get the most out of the games seem to be the makers of the games…

By: Eva Kiviranta on December 10, 2012

at 12:29 pm

Digital humanitarianism – Occupy and Sandy communication as disaster response.

One of the most fascinating entities in the ‘activist’ arena today is the Occupy Movement. From its specific and humble origins, and perceived extremism to now being an instrumental force in helping New Yorkers rebuild following Hurricane Sandy, this activist group, one could call dissident & helper.

We would agree that some groups are clearly dissidents and some are helpers. Some groups begin as one and morph into the other, or straddle the line between them. We see this type of evolution with the Anonymous as well, and is spoken to in Coleman’s article. Occupy represents itself very much as an anti- establishment organization, though even ‘organization’ they would disagree with. Though the ambiguity surrounding their actual affiliation is hard to decipher. Occupy Wall St states that it is “an affinity group committed to doing technical support work for resistance movements” and is not affiliated with Adbusters, anonymous or any other organization.

Occupy is a people’s movement, organically created, and increasingly precise in its action, leveraging technology to coordinate its collective actions. But Occupy is not just Occupy, it is in many different physical locations and in many different incarnations online. Perhaps more importantly for this conversation is that this loose amalgam of engaged citizens are pointing their energies to issues they feel are important. The mission of Occupy is fluid as is its membership, and we see this moving into concrete, social change and even disaster- response actions. These actions have brought the movement into a truly social sphere, one that has made deep connections to communities and provided important services and support to many in need.

Is the Occupy movement the future of the digital activism and will their presence in the established domains of non-profits change our collective perception of this type of community-based for one another. As we saw during the Sandy Hurricane, Occupy was (is) highly effective in coordinating communication, support, supplies, transportation involved in the aftermath of the storm, eclipsing the effectiveness of established NGOs (Red Cross) in delivering real-time help for their neighbors. Occupy become everyone. Many of my friends living in New York City, offered their time and vehicles and power supplies to those in need, and were able to do so efficiently due in part to the communication on social media disseminated by the OccupySandy group and the #OccupySandy phrase on twitter. These individuals do not call themselves ‘activists’ per se People contributed and then went on with their day, reading twitter, looking for the next opportunity to help with specific support, and thousands of others did the same. This phenomenon of coming together and receding and coming back and disappearing in a part of online community building, and more so of dissident activities than social movements in broad terms, but again those lines are becoming more difficult to discern. What are the ramifications of this?

Fascinating stuff to research, talk about, debate. Looking forward to seeing everyone tomorrow.

Matt

By: Matt Mitchell on December 10, 2012

at 3:07 pm

Italy also has an Anti-ACTA facebook fanpage (http://www.facebook.com/pages/Anti-ACTA-NO-ACTA-Dite-NO-ad-ACTA-Italia-Italy-Italian/128166037304492) but it is not much popular, altough I found it cited in some news articles that were about the protests in the streets.

As in other countries there is also a “pirate” political party Partito Pirata (http://www.partito-pirata.it/) founded in 2006 and based on the model of the Swedish Pirate Party.

There is also italian Indymedia page (http://italy.indymedia.org/) – but it seems it doesn´t work in this moment.

A group dedicated to Guerilla marketing in Italy: http://www.guerrigliamarketing.it for example fake UFO landing (http://www.guerrigliamarketing.it/intelligence/riccione.htm) that confused the media.

And I found an interesting example of “hacktivism” medium in Italy: The magazine Neural (www.neural.it) – an influential new media culture magazine (according to Wired) founded by Alessandro Ludovico in 1993. According to it´s Facebook page “Its topics are based on media art, especially the networked and conceptual use of technologies in art, hacktivism, meant as digital media activism, and electronic music, investigating experiments in music and technology, including the scattered galaxy of sound art.”

By: michaelarakova on December 10, 2012

at 3:42 pm

I as well dipped into the digital dissidents and media reformers already last week, as the division between media helpers/digital humanitarianism and digital dissidents seems like a fine line. My country, Morocco, has stepped into a new era with the very rapid growth in the use of the internet (especially amongst young people) and social media. What is incremental in the obvious case of the Arab Spring and media reform, is that the problems and need for uprising was already there, and the growing use of social media happened to coincide with the political stirring in a way, which triggered the enormous use of social media during the Arab Spring. Social media was used on a massive scale to voice out the opinions of groups without a strong voice to begin with (e.g women). Social media and the characteristics concerning the internet in general (rapideness, repeatability, fast spreading…) brought so much visibility and good exposure to the people’s will to reform the structures in society and demand for more open democracy and transparency in the government. As Rasha A. Abdulla states in his article linked in this blog post: “Social media prepared Egyptians for the revolution and enabled them to capitalize on an opportunity for change when the time came.”

These thoughts spread across the Arab world, in great parts thanks to social media. Also the social media brought along a feeling of personal experience and a sense of humanity, as people were not only faces or victims on the news – they were represented as individuals with their own names. The internet brought along a strong sense of community, which then densened into real-life actions – people on the streets with a common cause. An interesting term called “the spiral of silence” (Elisabeth Noelle-Neumann) may be of use here – a community of people might share the same thoughts but as their thought doesn’t not surface and appear in the public, they stay quiet and might let a single dominant opinion (e.g from a small but loud minority or well-organized group) take up space and become an accepted, hegemonic one. What I am thinking is that the internet might, due to its potential anonymity and low threshold for participation and expression, lower the odds of people staying quiet on issues they find important. There is always a group of people to agree with you on the internet, your organization and will for action and reformation determines the level of true revolution and change. (Plus of course the groups opposing your thoughts and goals, there is always negotiation for hegemony in public)

Another thought that came to mind on this weeks theme was from Banafsheh’s comment on digital activism being lower in countries with a high level of democracy. This would suggest that people become passive as citizens when a country hits a certain point of democracy, is it so? As we saw with hacktivism and the document We Are Legion, this would not be the case, but instead people start demanding further transparency and freedom of belonging to networks and acting in the internet (Wikileaks, Pirate Bay, demand for broadband internet as a civic right…). I would say that digital activism is different in modernized and democratic countries than the maybe radical activist movements for democracy in other countries, like Morocco. A question to ask is, is there a path for digital activism, different phases a country goes through (on the internet) on its way to democracy? In my country, in the case of Morocco, there was a long brewing discontent for the political system, which burst at the opportunity of exposure. This path is very much different from the one of Finland for example, where the demand for digital reformation is not that great.

By: annisn on December 10, 2012

at 4:04 pm

One of the most interesting sites linked to Hacktivism that originated from the United States is http://www.4chan.org. Gabriella Coleman claims in his article that the site, “is widely perceived to be one of the most offensive quarters of the Internet”. According to one Washington Post journalist, “the site’s users have managed to pull off some of the highest-profile collective actions in the history of the Internet.” (http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2010/08/09/AR2010080906102.html?hpid=topnews).

The website is basically an image-based bulletin board where anyone can post comments and share images. It has become infamous for creating some of the most memorable internet memes like the classic rickrolling and lolcats, but it has also been credited as the starting point of the Anonymous meme.

In response to the original posts pondering’s, I would have to admit that much like real-world communities, online communities can often be temporary and fleeing constructions. However, this is not always the case and I would be more inclined to conclude that in the case of hacktivism, it is often the communities campaigns that prove to be fleeing fads.

More to follow 🙂

By: chr1sdenholm on December 10, 2012

at 4:06 pm

Here are two nice one-liners from a NY Times story about censorship in Lebanon ((http://www.nytimes.com/2012/07/04/world/middleeast/lebanon-artists-confront-rise-in-censorship.html?_r=0)):

“In Beirut, the censors have banned “The Da Vinci Code” as anti-Christian and the TV series “The West Wing” as anti-Arab.”

““The majority of complaints are initiated by the churches,” Mr. Mhanna said. It is perhaps the only thing religious parties on all sides seem to agree on. “When it comes to censorship, they’re all perfectly O.K. with that.””

Lebanese censorship is apparently more active on traditional TV than on the web. It is claimed by some activists that the government keeps internet speeds down purposely (they are very low even compared to some countries in the area). Nevertheless, the political consensus with the help of the churches supports a moderate censorship which of course provokes digital activism. Here is a pretty nice example about the conversation that is going on in Lebanon these days. It’s a clip of a TV comedy about lebanese censorship bureau, watch the trailer: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nxEJQ4ebktQ – The show is not aired through TV but is only accessible in the web at mamnou3.com.

The Lebanese civil war never really ended (only the military operations did). On top of the inner conflicts Lebanon is surrounded by conflicts. As Hezbollah holds significant power in the country and because of the recent history, the relationship with Israel is understandably very bad. The Syrian situation on the other border is severe and also contributes to the tactics and goals of Lebanese dissidents. I tried to find information about the role of Lebanese digital activists in the Syrian crises but didn’t stumble upon anything interesting.

Some examples of activist bloggers and communities in Lebanon:

http://www.khalass.net/ (in arabic);

https://www.aswat.com/fr/node/1397

By: Johannes Koponen (@johanneskoponen) on December 10, 2012

at 5:28 pm

Media Reformers in Peru

In the report mapping digital media in Peru, they did not mention at all media reformers. However, social media has been used with dissidence purpose and it was noticeably important before the presidential election last year, when Facebook group and Twitter followers somehow give a measurement idea of the popularity of the presidential candidates. Still the use of internet and Social Media is growing in the country.

Regarding to the media reformers, I decided just to search through Google Peru what I could find in “my country” about reformers. I used the comments of others online mates in the google doc, just to find ideas of words that I could use to search. Well, initially and after watching the “We are Legion” documentary, I found that Peru have their own Anonymous group http://www.anonymousperu.com , this group have post mainly related to corruption, violence, protest, at least in the last few days. Additionally, I found a Facebook group against ACTA http://www.facebook.com/pages/No-a-La-Ley-Acta-O-Sopa-Peru/158064627638274

but it does not seem to be popular, not even very active page. Finally, I found something interesting that it was reported in a blog and it was related to the Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement, this agreement was also reported in the mainstream media (newspaper). This is a commercial agreement between Peru, Chile, Brunei, New Zealand, Singapore, Malaysia, US and Vietnam, which also include online regulations based on copyrights issues. There are already two Facebook communities that are calling against this agreement. Again, these two online communities seem to be very low active and popular. Perhaps, that is the reason why the report did not mention about media reformers. It is exist but it is still growing.

By: Lia on December 10, 2012

at 6:50 pm

Plenty of things to say, where to start??

I focused on Jansen’s chapters.

He discusses how in the 1980s one of the biggest protests had environmental grounds and was the fight against nuclear power. Well, the topic is still actual. In Japan, ‘my country’, the issue became topic of debate especially after the Fukushima disaster. Sayonara Nukes (http://sayonara-nukes.org/english/) was an initiative that aims at ‘saying good bye to nuclear plants’.

Jansen continues by introducing the topic of defamation. I think this is a rather delicate one, especially for the fact that what can be considered as defamation varies from country to country, from person to person. What, in my opinion, is interesting in Jansen’s arguments, is the term of defamation in relation of the so-called ‘whistleblowers’. A whistleblower is a person that sees something that can be considered wrong, such as corruption in an organisation, and reports what he/she saw to the bosses. Even though defamation can be an issue here, in the sense the accused person can just claim to be a victim of defamation by the whistleblower, there is a much bigger problem. Jensen cites Australian whistleblowers and the problem they have encountered. Generally, whistleblowers are harassed (because nobody likes a snitch, right?) and bosses, or authorities, hardly act on what had been reported by the whistleblowers.

Additionally, before the Web people who wanted to publicise their case had to rely on the media or send out copies of documents (proofs) by mail… that they had to pay for (of course…). In this sense, the Internet has brought along a great opportunity for people to speak up, and louder, across the Web and to an international ‘audience’.

Today many people have smart phones, with incorporated cameras, that can use to capture what is happening around them. Smart phones, tablets and portable devices (with a camera) appear to have strengthen what Jensen refers to as ‘subversion or empowerment’ (amateur monitoring the police and state activity), ‘inversive surveillance’ (watching the watchers) and ‘sousveillance’ (monitoring from the bottom). Ordinary people can take pictures or make videos or what is happening and share it across the web. Nowadays, how Rasha A. Abdulla says, the Revolution will be Tweeted. An event can be captured and shared on the Web in a relatively short time. If the content seems interesting for the mainstream media, then, as Gil Scott-Heron sang, the Revolution will be televised. Today the priority is on the Internet, because it is faster and can bring the information (article, picture, video) across the world in just a few seconds.

If one pairs the potential of sharing information online with what Gebe Sharp calls ‘political jiujitsu’ (if peaceful protesters are brutally assaulted, lots of people will see this as terrible and turn against the attackers), the power of sousveillance online is immense. Ordinary people can act as whistleblowers and if they notice something wrong, they can simply rely share their finds and information online.

The term of political jiujitsu brings me to anonymous. To some extent, this is what create Anonymous actions against white nationalist radiospeaker Hal Turner: he verbally assaulted someone on 4chan and some Anonymous members rushed in the victim’s defence. I really liked the documentary, because he discussed Hacktivism and Anonymous from inside (former and current members,…). The documentary brought to mind pretty much all the key concepts discussed by Jensen: the idea of whistleblowers, defamation and sousveillance.

A short note: I actually got the chance to pass by a Stop-ACTA protest last February in Stockholm and I saw dozens of people with the Guy Fawkes mask.

By the way, what did you guys think when, in the documentary, you heard people saying that in Israel there was a protest where Palestinians and Israelis members of Anonymous stood together and held each other’s flag? I thought it was incredible!

Anonymous has targeted Japan because of its new anti-piracy law (http://www.globalpost.com/dispatches/globalpost-blogs/the-grid/anonymous-declares-war-japan) and has launched cyberattacks to Japanese governmental websites (http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/technology-18608731). However, Anonymous has also Japanese members, who protested against the new copyright law by picking up litter in Tokyo (http://www.news.com.au/technology/masked-hackers-attack-rubbish/story-e6frfro0-1226420065106).

Analysing Japan I couldn’t find many examples of dissidents. There more relevant forms of protest can be date during the WWII period. After that, unions has been the organisations in the spotlight when it comes to protesting. One of the more recent case of Japanese dissidents are the people who take part at the ‘Sayonara Nukes’ rally. Just try to Google sayonara nukes and take a look at a couple of pictures to get an idea of the size of the protest..quite impressive!

An end note: Jensen discusses also the idea of the downloader of music as one of the first forms of digital dissidents. I actually wrote a paper about the issue of open Internet, copyright and the SOPA-PIPA debate. Here are a couple of good references:

Berry, D. M., 2008 Copy, Rip, Burn: The Politics of Copyleft and Open Source. London: Pluto Press

DiBona, C., Cooper, D., Stone, M. 2006 Open Sources 2.0: The Continuing Evolution. United States: O’Reilly Media

Dusollier, S. 2003 Open Source and Copyleft: Authorship Reconsidered? Columbia Journal of Law and the Arts 26 (2003): 281-296

If you are interested I have more, so don’t hesitate to ask!

By: yanngick on December 11, 2012

at 5:56 am

One thing I forgot to mention and that I would like to hear your opinion about… It is true that nowadays we have smart phones, etc. that allows us to ‘monitor’ what is happening around us and, if necessary, allows us to take pictures/make videos and share them on the Internet. Acting as digital whistleblowers seems to be a good thing to do, right? What do you think about what recently happened in NY? A man was pushed under the metro and a photographer managed to take a picture (that was later published on the front cover of the New York Post) just seconds before the metro ran over the man. My point leads to the concept of ethical photojournalism (http://www.forbes.com/sites/jeffbercovici/2012/12/04/new-york-posts-subway-death-photo-was-it-ethical/). If a Rodney King killing happened today and a ‘digital whistleblower’ watched the whole scene, what is the right thing to do? Intervene (try to stop the beating or in the NY metro case try to save the man), with possible endanger, or make sure not to be in a threat situation (not intervene at all), in order to be able to capture the whole thing on camera and let the world know what happened?

To conclude with a positive video, check this one about the positive things that surveillance can capture 🙂 http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Sf-HgH-Wvb0

By: yanngick on December 11, 2012

at 6:08 am

There was a big debate about this, but also in terms of how we as humans view death, and how disturbing it was to know that the man in the photo was about to die.

Here’s an interesting interview by Barbie Zelizer from Annenberg (has she been your lecturer i journalism studies?) http://www.slate.com/articles/news_and_politics/press_box/2011/01/deadly_images.html

(Debates about smartphone photo ethnics were discussed in relation to the shooting by the Empire State Bldg a few months past, when NYT and other published a bystander-capture photo of a bleeding victim).

By: mediastudies2point0 on December 11, 2012

at 8:13 pm

The photo debate reminds me the tragic story of Kevin Carter, who won a Pulitzer Prize for a photo he took of a starving Sudanese toddler stalked by a vulture and later committed suicide because of the emotional impact the experience had on him. http://www.fanpop.com/clubs/photography/articles/2845/title/kevin-carter-consequences-photojournalism

By: evelinan on December 14, 2012

at 3:26 pm

Moldova is obviously a good example of digital political activism. As I wrote under post for week 5, Moldova’s „Twitter revolution“ attracted world-wide attention after the presidential elections on April 5, 2009. Social networks & SMS were used for planning and Twitter during active street protests and the subsequent information war.

http://www.unimedia.md is one of the most popular news sites in Moldova. It is an online-only site, which started as a new aggregation site, but gradually increased its original content. It is considered by some to be „a largely pro-opposition media outlet“. During the 2009 elections, the government tried to close the website, but failed due to civil society pressure. http://www.zdg.md is an online version of Ziarul de Gardă, an independent newspaper in Moldova. The website offers the following description: „We specialise in investigative journalism, and are dedicated to shedding light on the widespread corruption, organised crime, poverty, social injustices, violations of human rights, and trafficking of people here in Moldova. Every week we publish new stories on these important issues, with the aim to inform the entire world about the realities of life in the country.“

In terms of spreading ideas, blogs by journalists and others are quite widely used. Unimedia.md has blogs by journalists & many journalists also have personal blogs.

At the same time, only 1/3 of people have access to internet and TV is used as the primary source of information, which rarely offer good quality analysis of social topics.

By: evelinan on December 14, 2012

at 3:39 pm